NSAttributedString and AttributedString Bridging Performance on macOS

With the introduction of the Swift-native AttributedString in iOS 15 and macOS 12, it’s become pretty common to convert between the existing NSAttributedString and the new type. Certain first-party frameworks, like SwiftUI and App Intents, require developers to use the new AttributedString. In existing apps, simply moving off of NSAttributedString can be too heavy of a lift, and if you’re using Objective-C at any point in the stack, such a migration simply wouldn’t be feasible. I also would be the last person to shame you for enjoying well-written Objective-C code.

Luckily, we can convert between AttributedString and NSAttributedString with the help of built-in methods. While it is fairly widely known that the bridging is not toll-free, as the types use distinct underlying representations, I haven’t found any comprehensive explorations or official first-party insight into exactly how fast or how slow such conversions are.

If you’ve worked in an established SwiftUI codebase, or if you maintain one of your own, you’ve likely seen code like this:

Text(AttributedString(viewModel.nsAttributedString))

As any experienced SwiftUI developer is likely to know, our views’ body computations should be as lightweight and cheap to execute as possible. AttributeGraph will ultimately decide when and how often to reevaluate the body, and putting accidentally expensive computations that should’ve been precomputed and cached inside a view model – or elsewhere outside the view – is likely one of the more common and easier to fix performance problems in SwiftUI view hierarchies.

Depending on just how expensive these conversions are, performance of our entire app could be at stake! Given the weight of the situation, exactly how concerned should we be when we see the bridging between the two attributed string representations? Are the performance characteristics the same for both directions of the conversion? How does the performance scale with the size of the strings?

Apple’s documentation does not provide a definitive answer. So, I decided to set up some performance tests on macOS 26.2 and try to find out. I’m posting the findings here hoping they could be of use to someone asking themselves similar questions.

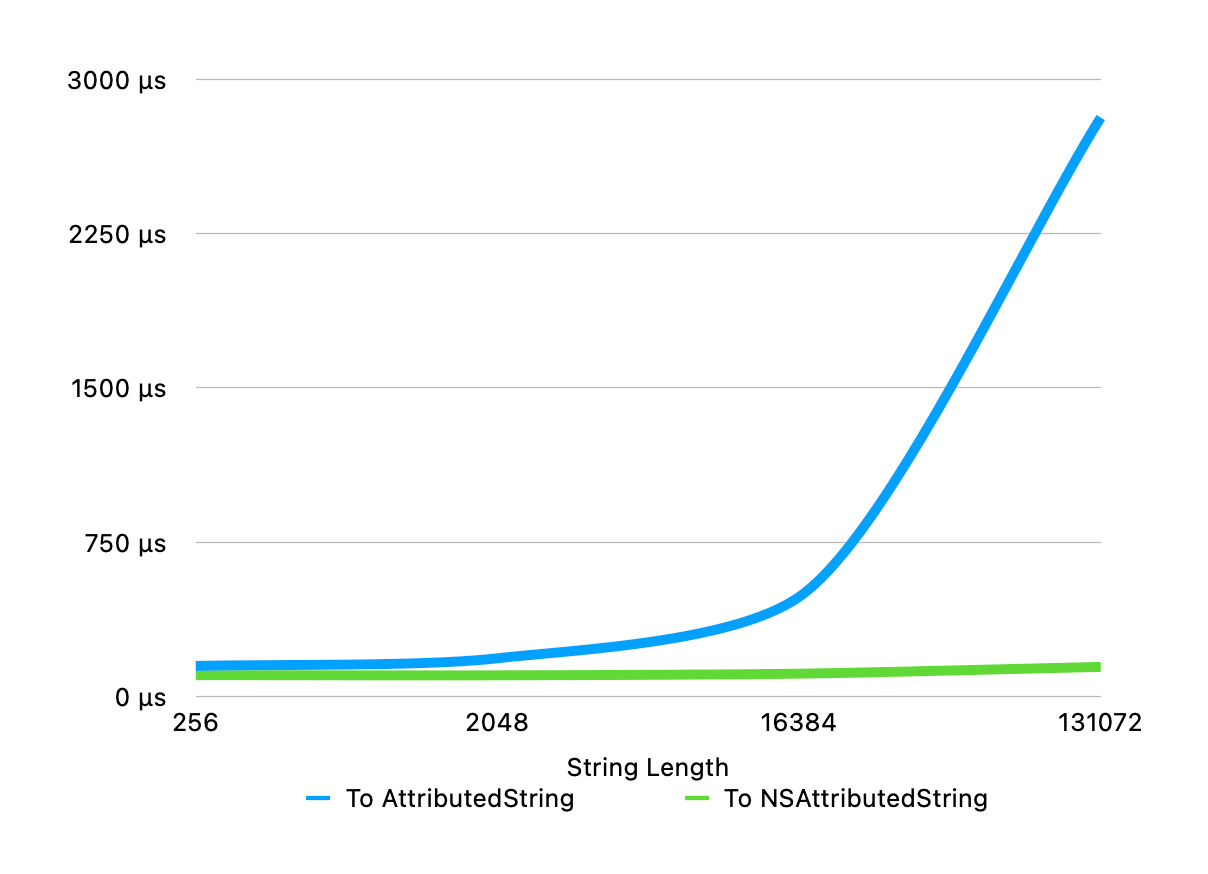

String length

In this test, I held the number of attributes per run (4) and run count (32) constant while increasing the length of the string.

| String Length | NSAttributedString to AttributedString |

AttributedString to NSAttributedString |

|---|---|---|

| 256 | 148.254 μs | 103.584 μs |

| 2048 | 185.604 μs | 102.726 μs |

| 16384 | 483.992 μs | 110.828 μs |

| 131072 | 2814.156 μs | 143.640 μs |

This shows that the cost of conversion from NSAttributedString to AttributedString scales strongly with length: 148.3 μs at 256 characters to 2814.2 μs at 131072 characters (about 19.0x). This raises concerns for code like the above Text(AttributedString(viewModel.nsAttributedString)), where the conversion happens on a hot path, especially if you can’t guarantee the string to be sufficiently small.

The other direction stays much flatter with length, rising from 103.6 μs to 143.6 μs over the same range. It seems to generally be a lot cheaper to convert an AttributedString to an NSAttributedString than the other way around.

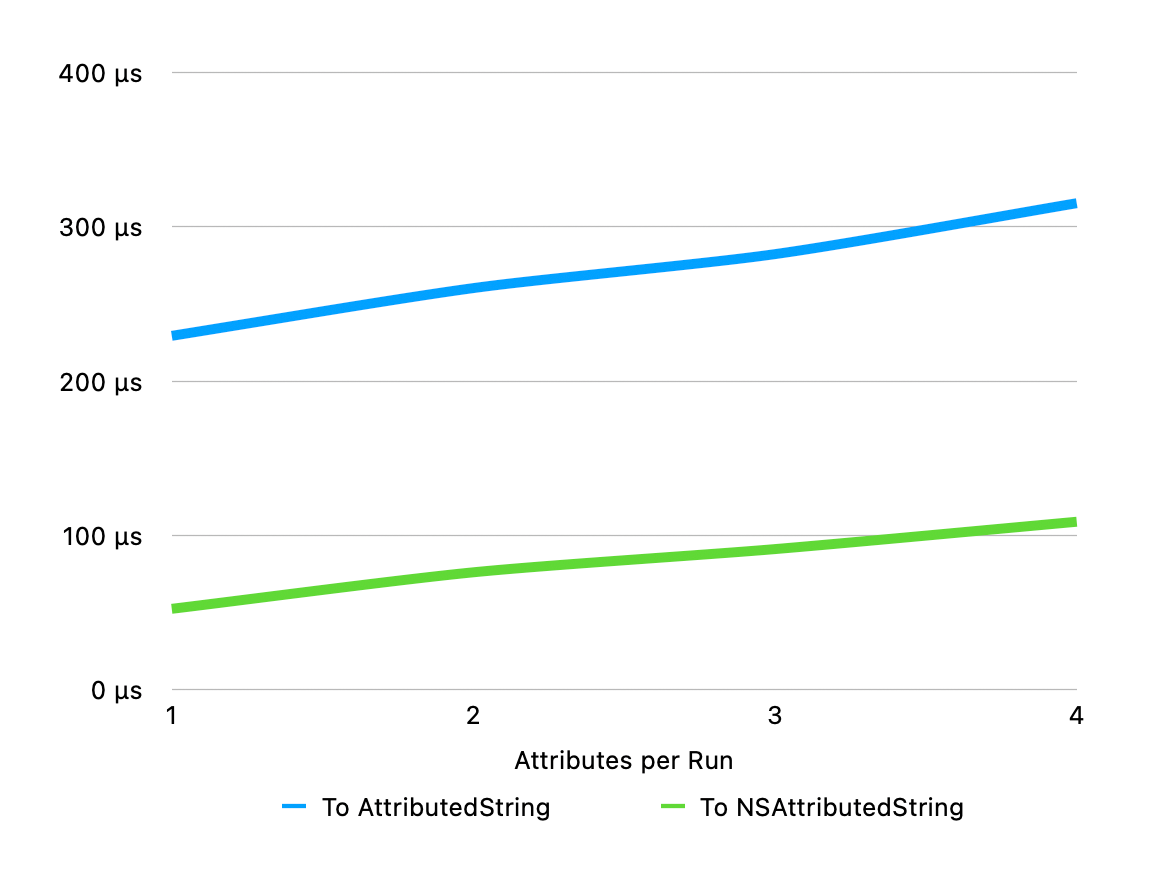

Number of attributes

The length of the string is not the only axis we may want to test when dealing with attributed strings. I wanted to see what happens if I held both the string length (8,192) and run count (32) constant while increasing attributes per run (1 → 4). This would show the sensitivity to “attribute richness” of the strings.

| Attributes per Run | NSAttributedString to AttributedString |

AttributedString to NSAttributedString |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 229.298 μs | 52.362 μs |

| 2 | 260.248 μs | 76.036 μs |

| 3 | 282.270 μs | 91.080 μs |

| 4 | 315.272 μs | 108.800 μs |

This shows a close to linear increase for both directions.

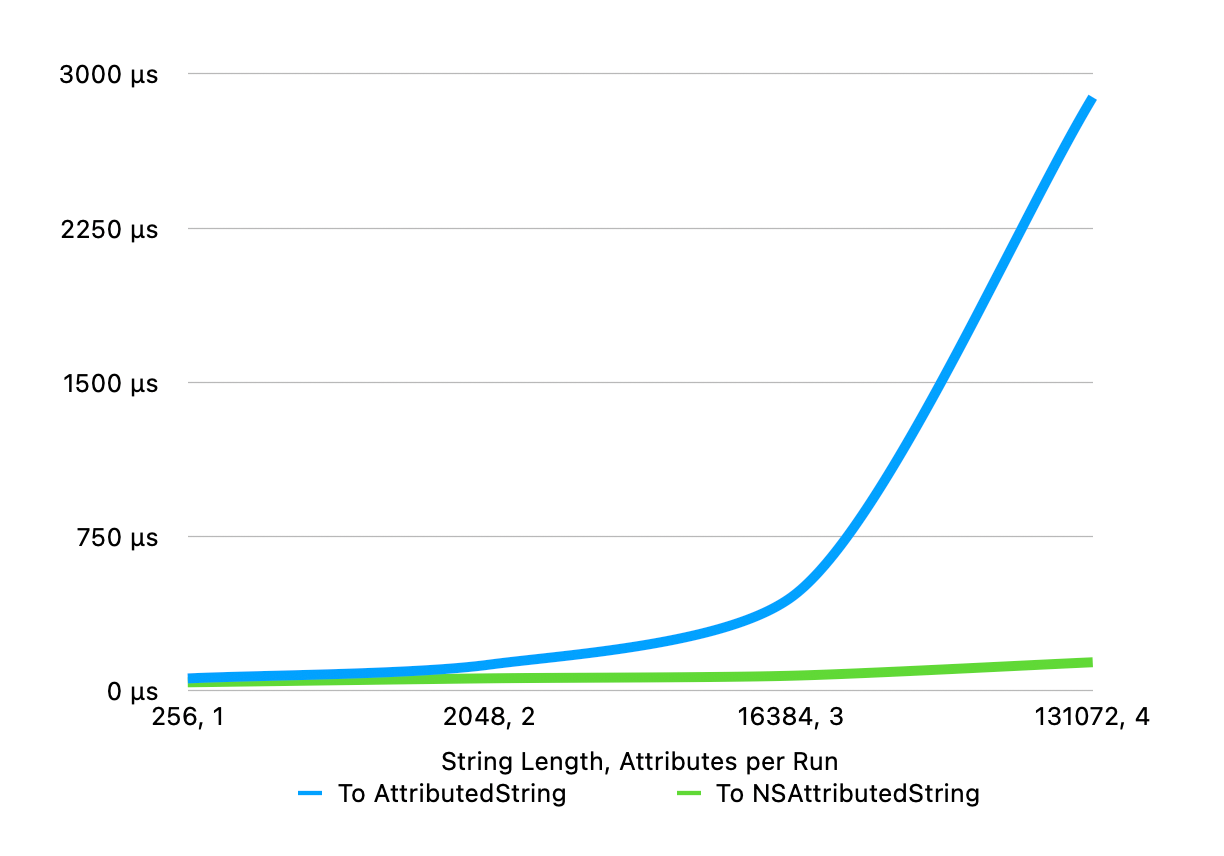

A combination

I also wanted to grow the length and attribute richness together to simulate a very frequent real-world scenario. Based on the above results, the hypothesis was that the growth would be dominated by the growth of the length of the string.

| String Length | Attr. / Run | NSAttributedString to AttributedString |

AttributedString to NSAttributedString |

|---|---|---|---|

| 256 | 1 | 61.008 μs | 41.972 μs |

| 2048 | 2 | 127.972 μs | 61.394 μs |

| 16384 | 3 | 454.824 μs | 74.008 μs |

| 131072 | 4 | 2886.374 μs | 139.574 μs |

The shape of the results is pretty much the same as what we saw when growing the length of the string, leading to very similar conclusions.

What this shows

The initializers of both AttributedString and NSAttributedString accepting the other representation are designed to be syntactically lightweight, but as we can see from this test, are not guaranteed to be. What this tells me is that I shouldn’t treat the work done by these conversion operations as trivial, and should therefore avoid cases where I perform a lot of these conversions on a hot code path like inside a SwiftUI view’s body, especially if I don’t know the length of the input string.

In SwiftUI

My practical recommendation here, solely based on the data above, would be as follows.

- If you’re dealing with very small strings, or strings of a deterministic but short length, it’s probably “fine” to keep converting them inline.

- It likely doesn’t matter how saturated with attributes the string is.

- If the string we’re working with is based on a user input or is otherwise of a nondeterministic length, convert it once.

- It is best to store the string as the representation you’re going to present at the View Model (or equivalent) layer. If you’re presenting via SwiftUI

Text, store the string as anAttributedString. - When the input value affecting the string changes, rebuild it.

- This way, you’re the one in control of how often the string conversion occurs.

- It is best to store the string as the representation you’re going to present at the View Model (or equivalent) layer. If you’re presenting via SwiftUI

What this doesn’t show

My goal with this little performance test was to see how converting between the two built-in attributed string representations performed on the current version of macOS (26.2). It was not meant to be a comprehensive test, since other platforms, devices, and OS versions may behave differently. Optimizations may be introduced at the framework level in the future. Similarly, the performance could regress, and surely both instances have happened in the past.